‘All happy families are alike: each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ This is the famous opening line of Anna Karenina, translated, of course, from Tolstoy’s original Russian. Wiser people than me have over the years applied what has come to be known as the ‘Anna Karenina principle’ to several fields of enquiry including ecology and statistics. And ancestors of the principle have been identified in the second law of thermodynamics – even in the writings of Aristotle.

But when thinking about family businesses I myself wonder. Certainly, many family businesses, when caught on the cusp of a crisis, assume that their problems are unique, can only be solved by themselves and are thus particularly intractable. But over years of working with family businesses in the field, in Europe, Asia and Africa, and with students of family business in classroom, I have seen the same sources of unhappiness arise time and time again. What explains this difference of perspective, and is it significant?

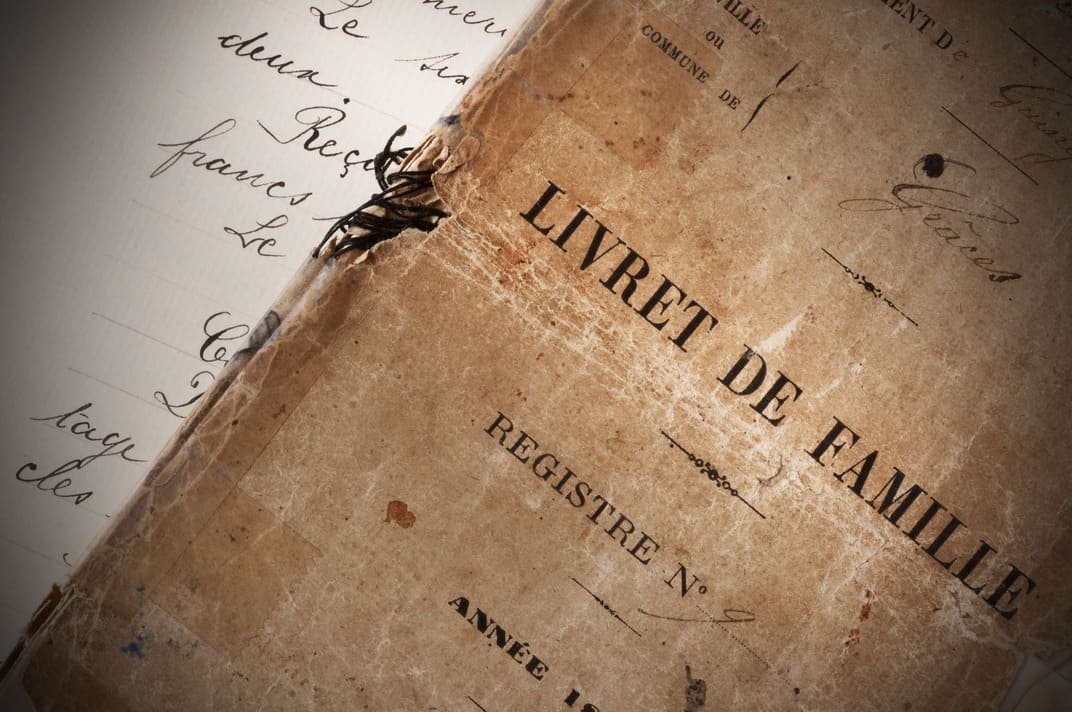

One reason is that the defining family business problems are inter-generational. They manifest themselves in particular in and around succession, both management and ownership succession. It follows therefore that for the members of a multi-generational family business the issue will typically arise only twice in a lifetime – firstly when you take over, and secondly when someone takes over from you. For the first-generation family business, the issue will never have presented itself before. What hasn’t happened to you before has the appearance of being unique, but succession is an experience that every family business has to confront, regardless as to which industry they are in or on which continent they are located. Family business advisers can attest to this as they wrestle with the problems of succession every day.

Another reason, also related to succession, is tied up in the fact that very few family businesses are created as a deliberate act. Entrepreneurs create businesses, they don’t create family businesses. True, many of us choose our life partners and set out to create families, but for most entrepreneurs the creation of a family business is something that just happens. One of the kids expresses an interest in the business, and the next thing you know is you’re worrying about succession. It is difficult enough to plan for the known unknowns in business. Family businesses have an additional category of unknown unknowns that complicate plans still further. And because the nature of the family business is so unexpected as well as unpredictable it can fool those closest to it into thinking their problem has never been seen before.

Other reasons are associated with family businesses’ experience of business growth. A growing business is a changing business. The challenges confronting an entrepreneur as she creates a business change as the business reaches stabilisation and then grows and matures further. The challenges presented by growth are many and varied and the involvement of family as well as founder will inevitably add a personal dimension that complicates things further, but they are not unique. But over the years, academics have repeatedly studied the change demanded by growth and have with some degree of success reduced it to series of generalisable phenomena.

These reasons are interconnected, not least through the inevitability of the event of succession, so addressing them demands a multidimensional perspective. For example, every entrepreneur needs to accept that the element that perhaps needs the most consideration as the business passes from one stage of development to another is his own role. It has been many times observed that good entrepreneurs often don’t make good CEOs because the strengths of one are often weaknesses in the other. Those that do succeed in the transformation are those who have acknowledged the need to manage the delegation of elements of their roles to others as the business has extended its reach and redefined its purpose and the market into which it has sold product or service has evolved. For many founders change actually means exit – which in part is an acknowledgement that entrepreneurs are better at one type of role than another. For founders of the family business the challenge doubles up; the easy solution when looking for a successor is for family business founders to look for qualities in potential successors that they see in themselves. It’s an understandable instinct particularly for a parent worrying about the management of growth and the implications of ownership and management succession. You look along the line of children lined up at the table for Christmas lunch and wonder which one is going to be the one to take your job. Surely you should look for a chip off the old block? But the business will in all likelihood already be demanding something – someone – different.

Family business challenges, like growth challenges, are often internal challenges rather than external challenges. Businesses looking to strategic perspectives for solutions are looking in the wrong direction. Looking to strategy for a solution to an internal problem is just trying to blame someone or something else. Family business leaders should first look inside the business to management capability and capacity, structure and governance – though they are advised to benefit from an outsider’s perspective. A well-structured, properly functioning board, including the appointment of a non-executive director with experience of both succession in family businesses and the change demanded by growth will help, so will an experienced adviser. After all, what is ‘experience’ if it isn’t the benefit of having seen the same sort of problem before?

One other thing such an experienced non-executive or adviser might observe is that, though the growth and succession problems facing family businesses might be fairly generic, and the processes towards a solution fairly similar, the resulting happy family businesses are often very different from each other. Indeed, pace Tolstoy, family businesses find opportunities, and thus happiness, in all sorts of different places – even in the way they conceive of themselves as family businesses: some as owners happy to delegate management, others as active owner-managers, still more happy to pass on ownership as long as they can retain significant management control.

The more I think about it, I suspect that, although the Anna Karinina principle might make sense when translated into the language of statistics, ecology or physics, it might not actually make much sense when translated into the language of business – or when just applied to families.

Rupert Merson

Rupert Merson is an Adjunct Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at London Business School where he teaches a course on Family Business, and runs his own firm of adviser, Rupert Merson LLP. He has worked with family businesses in Africa and Asia as well as in the UK and Europe. An earlier version of this piece was written for the LBS StartHub in September 2020.